How wide is the net?

On drug selection for IRA negotiation

We are starting to see companies blame the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) drug pricing provisions for development decisions (specifically pipeline discontinuations). There seem to be largely two schools of response to these public statements: “see, we told you the IRA would harm drug development” and “companies are just using it as an easy excuse”.

I think the truth is likely some combination of the two, but I wanted to get into the specifics a bit more here.

First, the easy one- companies absolutely have a perverse incentive to use the IRA as an easy target for explaining negative decisions, much in the way they used Covid. It is easy to point to (potentially even politically expedient to do so) and no one can prove you are lying without seeing your internal model, which is, well internal. So even if development is reduced by the IRA (which I believe it will be at some margin), we should not take IRA finger-pointing as truly reflecting the law’s impact.

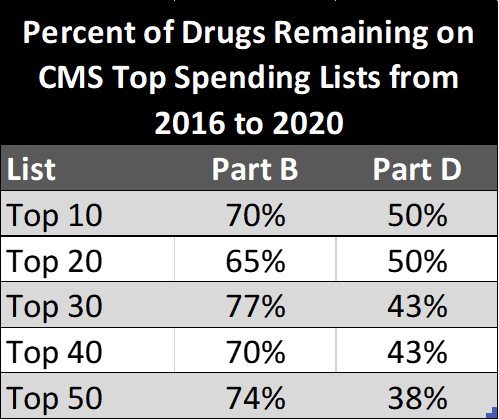

Now, the harder one. There seems to be some sentiment that these excuses have to be completely fruitless because assuming the drug meets IRA drug negotiation criteria also means assuming it will have blockbuster sales that land it on that list. I am not sure I buy into this one either. To think through it, I did a quick analysis of the top 50 Medicare Part B and D drugs by spend in 2016 and 2020 using CMS data and looking at what the churn rates of drugs in the top 50 were over those 5 years.

Above are the percent of drugs that remain on the top lists (at various cutoffs) from 2016 to 2020. This equates to a churn of 1.4 drugs/year for Part B and 2 drugs/year for Part D in the top 20 list and 2.6 drugs/year and 6.2 drugs/year on the top 50 list, respectively. In other words, there isn’t much movement in what drugs constitute top spenders from year to year, especially in contrast to the 15-20 drugs/year that can be negotiated under IRA after 2027. It is safe to assume that CMS could go “deeper” in the [anchored to today] list if it is looking to maximize use of the negotiation provision. This means the selected 15/20 of the future is likely to be lower in annual spend than the drugs on the initial lists, all else held constant.

When looking at the list I do not think it is a stretch to see sub-blockbuster drugs potentially being targeted. For example, the 20th drug for Part B and D in 2020 was Sandostatin LAR Depot at $445m in sales and Novolog Flexpen at $1.49B; The 40th drug was Fluad Quadrivalent at $232m and Tresiba $917m, respectively. And this is without filtering for negotiation eligibility criteria.

I took a very conservative (and easier) approach by not removing anyineligible drugs from the top 50 list such as those on the market for less than 9 (small molecule) or 13 (biologic) years, those with multiple sources, single orphan status indications, and so on. As a result, the sales figures for the top 20/40 eligible drugs in a given year will be lower than what is presented here. Application of these criteria could on its own be potentially significantly as well (a quick glance at the part B list has several IOs in the top 20, none of which meet the years on market requirement for the first negotiations). Given the results above and these conservative assumptions, it seems to me multi-hundred million dollar per year drugs could very well fall under CMS’ radar under the remit they are given, especially once we are a few years into the IRA negotiations.

So is a multi-hundred million dollar peak sales product that is about to enter phase III still NPV positive when the out year revenue is cut off by IRA? It all depends on the details of course, but take a small molecule that is expected to make $500m/year (peak sales) for three years ($1.5B total) beyond the 9 in which IRA could kick in. Let’s assume it will be targeted for negotiation and the discount comes to 50% bringing the cumulative sales in years 10, 11, and 12 to $750m instead of $1.5B. Discounted at 8% and assuming a median launch trajectory with regards to achievement of peak sales, this $750m differential is a ~$300m reduction to the NPV. Enough to stop development today? For some drugs, surely.

Of course there is a lot to be seen with regards to implementation including how drugs are selected, on what basis value assessments are made, how deep discounts are, and so on. And that clarity will improve the assumptions in NPV models and give everyone more clarity on exact impact on R&D (although we shouldn’t take companies’ word for it!). But from what I can tell, the assumption that only mega blockbusters will fall under the scope is wrong - unless CMS chooses to negotiate less than they are able to under the law. Hardly a reasonable assumption for someone creating the NPV model in assessing these opportunities today.

p.s. happy to share my excel sheets with data/calculations to anyone interested (leave a comment or message me on Twitter); and keep me honest on the math if you notice any errors!